Study: Resistant starch may help prevent some cancers in people with Lynch syndrome

This study looked at whether a type of nutrient known as resistant starch could lower the risk of cancers in people with Lynch Syndrome. Researchers found that resistant starch can reduce the risk of non-colorectal cancers but not colorectal cancer. (Posted 10/17/22)

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Contents

| What is ? | Guidelines |

| What is resistant startch? | Questions for your doctor |

| Study findings | Clinical trials |

| Strengths and limitations | Get support |

| What does this mean for me? | Related resources |

STUDY AT A GLANCE

What is this study about?

This study is about whether resistant starch in a diet can reduce the risk of colorectal or other non-colorectal cancers in people with .

Why is this study important?

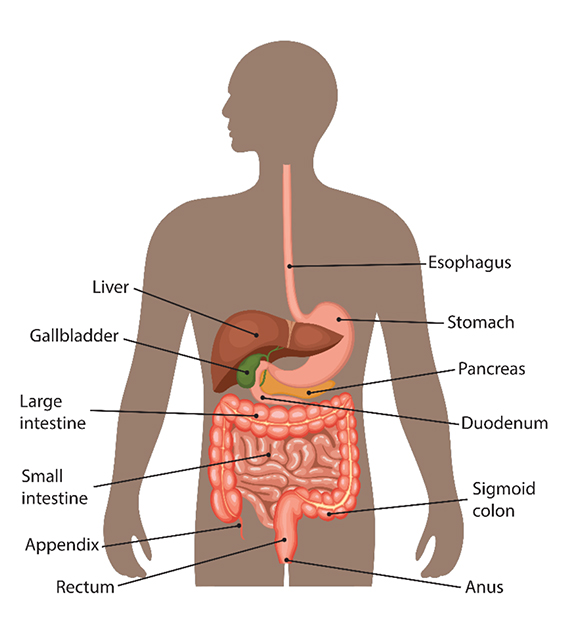

People with have an increased risk for various cancers, such as colorectal, endometrial, upper gastrointestinal (GI), pancreatic, bile duct and others. The upper GI tract (food pipe) includes the esophagus, stomach and the first part of the small intestine or duodenum (see image below). Upper GI cancers can be found in these organs as well as the pancreas and bile duct.

Screening for upper GI, pancreatic and bile duct cancers can be challenging. The survival rate for these cancers tends to be lower than for other Lynch syndrome-associated cancers. Therefore, it’s important to find better prevention measures, particularly for non-colorectal GI cancers.

What is ?

is caused by an in one of five genes:

People with have an increased risk for colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, stomach, small intestine, pancreatic, bile duct, urinary tract, brain and skin cancers; the risks for these cancers vary depending on the gene. For this reason, people with are encouraged to speak with a genetics expert to understand their risk for different cancers.

What is resistant starch?

Starch is a nutrient in food. Most starch is broken down in the small intestine into sugar, which the body uses for energy. Resistant starch is a type of starch that cannot be broken down in the small intestine. It is passed on to the large intestine where it is partially broken down with the help of gut bacteria. Resistant starch can be found in bananas, potatoes, grains, beans, peas, seeds and other foods.

There is strong evidence that a higher intake of dietary fiber lowers the risk of colorectal cancer and other diseases in the general population. Because resistant starch, which is a component of dietary fiber, is broken down in the large intestine by gut microbes, researchers wanted to know whether this is a way that dietary fiber may protect against colon cancer, specifically in people with .

Study findings

Researchers looked at people with who had inherited a mutation in , and . In this study, any Lynch syndrome-associated cancers outside of the colon and endometrium are referred to as non-colorectal cancers.

Participants consumed 30 grams (about one-quarter cup) of resistant starch (Novelose) or (cornstarch) for up to four years. For comparison, one cup of green peas has about four grams of resistant starch. Resistant starch powder was mixed into food or drink.

Participants were randomly placed into one of two treatment groups:

- resistant starch (463 participants)

- cornstarch (455 participants)

- Cornstarch is different than resistant starch. For this study, cornstarch was used as a for participants who did not receive resistant starch.

Colorectal Cancer Outcomes

- After 20 years of follow-up, there was no difference between the effects of resistant starch and on new cases of colorectal cancer.

- 52 (11%) participants were diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the resistant starch group.

- 53 (11%) participants were diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the group.

Non-Colorectal Cancer Cancer Outcomes

- After 20 years of follow-up, there were fewer non-colorectal cancers in the resistant starch group than in the group.

- 27 (6%) participants were diagnosed with non-colorectal cancer in the resistant starch group.

- 48 (11%) participants were diagnosed with non-colorectal cancer in the group.

- This was particularly true for cancers of the upper GI tract.

- 5 (1%) participants were diagnosed with cancers of the upper GI tract in the resistant starch group.

- 21 (almost 5%) participants were diagnosed with cancer of the upper GI tract, pancreas or bile duct in the group.

Non-colorectal cancer outcomes by treatment group

| Cancer Site | RS | |

| Endometrium | 15 (3%) | 16 (4%) |

| Urinary | 5 (1%) | 10 (2%) |

| Ovary | 2 (<1%) | 5 (1%) |

| Brain | 2 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) |

| Bile duct | 0 | 3 (<1%) |

| Pancreas | 3 (<1%) | 8 (2%) |

| Non-colorectal GI | ||

| Stomach | 1 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) |

| Duodenum | 1 (<1%) | 7 (2%) |

| Total Non-colorectal GI plus pancreas and bile duct | 5 (1%) | 21 (4.5%) |

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- This study followed participants for many years, meaning that the effect of long-term treatment on cancer rates would more likely be recognized.

- The study was well-designed, making the results more trustworthy.

- The study focused on people with , meaning that any results should be relevant for most people with .

- Researchers tracked many different cancer types linked to .

Limitations

- Because the number of cancers among participants is small, it is difficult to make a strong conclusion about any one cancer type.

- Researchers tested only a few participants in the resistant starch group to verify that they had taken the starch. Therefore, it is unclear how many participants took resistant starch and for how long.

- In studies involving diet, the foods that participants eat or don’t eat cannot be controlled. This could affect the study results. Randomizing the study helps to limit this somewhat.

- No mention was made of other patient characteristics such as race, BMI, exercise level and diet history. No analysis was performed to account for any of these factors that could affect cancer risk.

- The study did not address the variation in dietary patterns that occurs in different countries (e.g. South Africa and Finland).

What does this mean for me?

Overall, the result of this study does not change clinical care or risk-reducing decisions for people with . While it suggests that adding resistant starch may help reduce non-colorectal upper GI cancers, more studies are needed to confirm this observation. However, it is exciting to see that future non-invasive prevention measures may be possible for people with .

If you have , you may want to talk with your doctor to see if incorporating more resistant starch into your diet is appropriate.

Reference

Mathers J.C., Elliot F, Macrae F, et al. Cancer Prevention with Resistant Starch in Patients in the CAPP2-Randomized Controlled Trial: Planned 10-Year Follow-Up (Cancer Prevention Research 2022; 1;15(9):623-634.

Disclosure: FORCE receives funding from industry sponsors, including companies that manufacture cancer drugs, tests and devices. All XRAYS articles are written independently of any sponsor and are reviewed by members of our Scientific Advisory Board prior to publication to assure scientific integrity.

Share your thoughts on this XRAY review by taking our brief survey.

posted 10/17/22

IN-DEPTH REVIEW OF RESEARCH

Study background

Dietary fiber is part of plant-derived foods that cannot be completely broken down in the digestive system. Many studies have looked at whether dietary fiber can lower the risk of colorectal cancer in the general population. Generally, dietary fiber has been shown to lower the risk of colorectal cancer, but this protective effect is lost when other dietary factors are considered. So the effect of dietary fiber is unclear. Aside from colorectal cancer, a higher intake of dietary fiber can lower the incidence of heart disease, liver cancer and generally lower the risk of death from cancer.

While increasing the amount of dietary fiber has been linked to reduced risks of colorectal cancer and some non-colorectal cancers, the part of dietary fiber responsible for this improvement is unknown. Dietary fiber includes insoluble fiber that is undigested, while soluble fiber which is partially digested in the large intestine. Although resistant starch is not a fiber—it is a type of starch—it is often considered to be a component of dietary fiber.

Little is known about how resistant starch may prevent colorectal cancer and non-colorectal cancers in people with . This study looked at the effect of resistant starch and the risk of colorectal and non-colorectal cancers in people with .

This study reports on some of the data from the Colorectal Adenoma/Carcinoma Prevention Program 2 (CAPP2) study, a first-of-its-kind effort that was designed to test whether daily aspirin and/or daily resistant starch prevents colorectal cancer in people with .

Researchers of this study wanted to know

There are limited options to lower the risk of non-colorectal cancers such as cancers in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract in people with . Researchers of this study wanted to know whether incorporating resistant starch into the diet of patients would lower their risk of colorectal and non-colorectal Lynch syndrome-associated cancers.

Populations looked at in this study

The participants were people who were over age 25 and with . Participants had an in , and/or (people with or mutations were not included in this study) or were members of a high-risk family according to the Amsterdam diagnostic criteria for . This is a set of diagnostic criteria used by doctors to diagnose in individuals who have not had genetic testing.

Participants included people from Northern Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia and Hong Kong, Southern Europe (the Iberian Peninsula and Italy), South Africa and the Americas.

Participants who had previously been cured of cancer and still had their colon were also eligible. Colonoscopy and clearance of any found were prerequisites within three months of study recruitment. Patients diagnosed with bowel cancer were excluded for a year if their tumor was Duke A (cancer only in the mucosa or cell lining of an organ such as the stomach), two years if their tumor was B (cancer that has advanced to the outer layer of cells of the stomach but not to the ) and five years if their tumor was C (positive ) or D ().

Study design

This was a double-blind study. To ensure that neither participants nor researchers knew who was getting resistant starch, cornstarch (an inactive alternative to resistant starch) was used as a .

Participation included a colonoscopy at study entry and exit after two years, in addition to routine screenings. Participants were treated daily for two years with 30 grams of resistant starch (called Novelose) or (cornstarch taken in two separate doses). After two years, participants had the option to continue for two more years. After that, some participants consented to have a follow-up of 10 years or more, up to 20 years.

Participants were placed randomly (via computer) into one of 2 treatment groups:

- Resistant starch: 463 participants

- (cornstarch): 455 participants

At the end of treatment and through long-term follow-up, researchers gathered information on whether participants were diagnosed with colorectal cancer or other Lynch syndrome-associated non-colorectal cancers.

Study findings

The analyses presented below presents data for the entire CAPP2 cohort at 10 years as well as at 20 years for participants in England, Finland and Wales. Information on cancer diagnoses was obtained from national cancer or clinical registries.

The aspirin results from this study, presented previously, have already changed the standard of care for people with in the United Kingdom (UK). Based on the results of the study, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK now recommends that people with take daily aspirin for more than two years to prevent colorectal cancer. Read more in our XRAY review here.

Colorectal Cancer Outcomes

- 52 participants developed colorectal cancer in the resistant starch group; 53 participants developed colorectal cancer in the group

- Analysis showed no effect of resistant starch on colorectal cancer incidence.

Non-Colorectal Cancer cancer outcomes

- There were 27 non-colorectal cancers in the resistant starch group and 48 in the group.

- Resistant starch was found to have a significant protective effect for multiple, non-colorectal, Lynch syndrome-associated primary cancers.

- This effect was especially strong for cancers of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including stomach, duodenal, bile duct and pancreatic cancers.

- The resistant starch group developed 5 upper GI cancers; the group developed 21.

- This effect was especially strong for cancers of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including stomach, duodenal, bile duct and pancreatic cancers.

Non-colorectal cancer outcomes by treatment group

| Cancer Site | RS | |

| Endometrium | 15 (3%) | 16 (4%) |

| Urinary | 5 (1%) | 10 (2%) |

| Ovary | 2 (<1%) | 5 (1%) |

| Brain | 2 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) |

| Bile duct | 0 | 3 (<1%) |

| Pancreas | 3 (<1%) | 8 (2%) |

| Non-colorectal GI | ||

| Stomach | 1 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) |

| Duodenum | 1 (<1%) | 7 (2%) |

| Total Non-colorectal GI plus pancreas and bile duct | 5 (1%) | 21 (4.5%) |

All Cancer Outcomes

- Resistant starch was not protective when all cancers (colorectum, endometrium, , ovary, kidney/ureter, stomach, bladder, small intestine, pancreas, bile duct and brain) were looked at together.

- Resistant starch was protective in patients who had multiple primary Lynch syndrome-associated cancers.

- Resistant starch slightly prevented Lynch syndrome-associated cancers at 10 years, but this was most evident at the 20-year follow-up.

Non-Lynch syndrome cancer outcomes

- During follow-up, 45 non-Lynch syndrome-associated cancers were diagnosed in patients taking resistant starch; 44 non-Lynch syndrome-associated cancers were diagnosed in patients taking a .

- Resistant starch did not affect the risk of non-Lynch syndrome cancers.

The researchers were surprised when the trend of reduced colorectal cancer risk that was shown in participants who had daily resistant starch in previous studies did not occur in this study.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- Participants were followed for up to 20 years, meaning that the long-term treatment effect on cancer risk would be more apparent.

- The randomization of participants and study design strengthened the study, making the results more trustworthy.

- The study focused on people with , meaning that the results should be relevant for most people with . Although no participants had a or mutation, the effect of resistant starch on people with who have these mutations is unknown.

- Researchers tracked many different cancer types for which people with have a high risk.

Limitations

- The numbers of non-colorectal cancer cases were too small to make conclusions for a specific site.

- The estimated dose of resistant starch was 13.2 grams compared to the habitual intake of 4.2 grams per day in Europe. This larger amount caused considerable bloating in participants.

- The consistency between databases and registries is generally too low to confirm cancer diagnoses.

- Researchers did not show why resistant starch lowers the risk of upper GI cancers.

- The number of study participants was small; therefore it is difficult to make a strong conclusion.

- Researchers did not perform compliance testing for all of the participants to verify whether they took the required doses of resistant starch.

- In studies involving diet, the foods that participants eat or don’t eat cannot be controlled. This could affect the study results. Randomizing the study helps to limit this somewhat.

- Researchers made no mention of other patient characteristics such as family history, race, BMI, exercise level and diet history.

- The study did not address variations in dietary patterns in Eastern vs Western countries.

Context

Many studies have looked at whether dietary fiber can lower the risk of colorectal cancer in the general population. Generally, dietary fiber has been shown to lower this risk, but this protective effect may be lost due to other dietary factors. Aside from colorectal cancer, a higher intake of dietary fiber can lower the incidence of heart disease, liver cancer and lower the risk of death from cancer more generally.

Population-based studies that assess how dietary fiber may lower the risk of upper GI cancers are lacking. Studies that have been done show that higher dietary fiber may lower the risk of stomach and pancreatic cancers. A Japanese study also showed that higher amounts of dietary fiber may lower the risk of lower bile duct cancer. In another study, researchers saw that higher dietary fiber was associated with reduced intrahepatic (a network of small tubes that carry bile inside the liver to the duct) bile duct cancer. This data is promising but limited.

Resistant starch and dietary fiber may lower cancer risk by slowing cell growth in parts of the colon and changing the expression of genes that block cancer growth. Many different types of bacteria in our gut consume resistant starch. These bacteria produce substances that stop cancer cell growth and kill cancer cells after they consume resistant starch. These substances can also affect the immune system, which plays a large role in the development of cancer.

Conclusions

For people with , resistant starch does not alter colorectal cancer risk, but it does lower the risk of non-colorectal Lynch syndrome-associated cancers, especially upper GI cancers. Since screening, diagnosis and management of these cancers are difficult, this finding could lead to a change in the standard of care for people with to help reduce their risk for upper GI cancers. It is important to continue to study this association with more people with as well as the general population to determine whether resistant starch and dietary fiber reduce the risk of GI cancers in the broader non-hereditary cancer population.

Share your thoughts on this XRAY review by taking our brief survey.

posted 10/17/22

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) provides risk management guidelines for people with mutations.

Colorectal cancer

- Colonoscopy every 1-2 years. Speak with your doctor about whether you should be screened yearly or every two years. Men, people over age 40 and individuals with a personal history of colon cancer or colon may benefit most from yearly screenings.

- For people with , or EPCAM:

- beginning between ages 20-25 (or 2-5 years before the earliest age of colon cancer in the family, if diagnosed before age 25).

- For people with or PMS2:

- beginning between ages 30-35 (or 2-5 years before the earliest age of colon cancer in the family, if diagnosed before age 35).

- For people with , or EPCAM:

- Daily aspirin can decrease the risk of colorectal cancer. The best dose and timing are unknown. Speak with your doctor about the benefits, risks, best timing and dose.

Endometrial and ovarian cancer

- Be aware of endometrial and ovarian cancer symptoms.

- Consider endometrial biopsy every 1-2 years beginning between ages 30-35.

- Discuss the benefits and risks of oral contraceptives.

- Consider risk-reducing hysterectomy; discuss risk-reducing removal of ovaries and with your doctor (, , and gene mutations).

Stomach and upper GI cancers

- Begin screening for stomach cancer and other upper GI cancers between ages 30-40 every 2-4 years for those with , , , mutations. Screening should include high-quality upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodendoscopy, EGD), ideally at the time of colonoscopy.

- Consider earlier, more frequent screening based on family history of stomach or upper GI cancers.

- Test for H. pylori at the beginning of screening and treat if the test is positive.

Other cancers

- Consider annual cancer screening with testing and digital rectal exam.

- For people with a family history of urothelial cancer and men with an mutation:

- Consider annual urinalysis beginning between ages 30-35.

- For people with a family history of pancreatic cancer:

- Consider annual cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and/or endoscopic (EUS) beginning at age 50 or 10 years before the earliest age of exocrine pancreatic cancer in the family.

- Consider participating in a pancreatic cancer screening study.

- Consider annual physical and neurological exams.

Updated: 09/26/2025

- Is my family or personal medical history suggestive of ?

- Should I have genetic testing for ?

- Should I consult a dietician about my dietary fiber intake?

- Should I increase my dietary fiber intake? If so, how?

- How should I be screened for cancers?

The following screening and prevention studies are open to people with .

Colorectal cancer

- NCT05410977: Collecting Blood and Stool Samples to Detect Colorectal Cancer or Precancerous in Patients, CORAL Study. This study will determine the effectiveness of a screening technique, multitarget stool testing, for the detection of colorectal cancer in individuals with .

- NCT05396846: My Best GI Eating Study. This study will test three different diets in people who are overweight and who have an increased risk of colorectal cancer. The study will look at whether these diets improve eating and possibly lead to weight loss.

- NCT05411718: Studying the Use of Naproxen and Aspirin for Cancer Prevention in People with . The study will measure the effect of naproxen or aspirin on the immune cells in the gastrointestinal tract of people with . The trial will also evaluate any symptoms from the medications and any other changes of the colon and rectum.

-

NCT06708429: X-Talk of Enteral Mucosa With Immune System (LYNX-EYE). This study will collect samples from blood, the lining of the intestinal tract, mucosal-based, and hair to look at the connection between the immune system and cancer risk in people with .

Gynecologic cancers

- Validating a Blood Test for Early Ovarian Cancer Detection in High-risk Women and Families: MicroRNA Detection Study (MiDE). The goal of this effort is to develop a clinical diagnostic test to detect early-onset ovarian cancer, as currently, no reliable screening or early-detection tests are available.

cancer

- NCT03805919: Men at High Genetic Risk for Cancer. This is a cancer screening study using in high-risk men is open to men with and other mutations.

- NCT05129605: Cancer Genetic Risk Evaluation and Screening Study (PROGRESS). This study looks at how well MRI works as a screening tool for men at high risk for cancer. Enrollment is open to men with an in , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , and other genes.

Pancreatic cancer

- NCT03568630: Blood Markers of Early Pancreas Cancer. This pancreatic cancer study involves blood samples taken over time to identify biomarkers of pancreatic cancer in high-risk people. Enrollment is open to people with certain mutations linked to increased cancer risk.

- NCT03250078: A Pancreatic Cancer Screening Study in Hereditary High-Risk Individuals. The main goal of this study is to screen and detect pancreatic cancer and precursor lesions in individuals with a strong family history or genetic predisposition to pancreatic cancer. and magnetic cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP) will be utilized to screen for pancreatic lesions.

Updated: 10/03/2025

FORCE offers many peer support programs for people with inherited mutations.

- Our Message Boards allow people to connect with others who share their situation. Once registered, you can post on the Diagnosed With Cancer board to connect with other people who have been diagnosed.

- Our Peer Navigation Program will match you with a volunteer who shares your mutation and situation.

- Our moderated, private Facebook group allows you to connect with other community members 24/7.

- Check out our virtual and in-person support meeting calendar.

- Join one of our Zoom community group meetings.

Updated: 09/21/2025

Who covered this study?

Healio

Fiber supplement may help prevent certain types of hereditary cancer

This article rates 3.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 3.0 out of

5 stars

Interesting Engineering

Resistant starch can reduce hereditary cancer risk by 60 percent

This article rates 1.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 1.0 out of

5 stars