PUBLISHED: 19th November 2021

Presented by Erika Stallings and Dena Goldberg, CGC

It’s important for everyone to know their family history and their risk for cancer. This is particularly true for Black people who face significant health disparities related to cancer. Black women are more likely than white women to be diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 50, are more likely to have triple-negative breast cancer and are more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage.

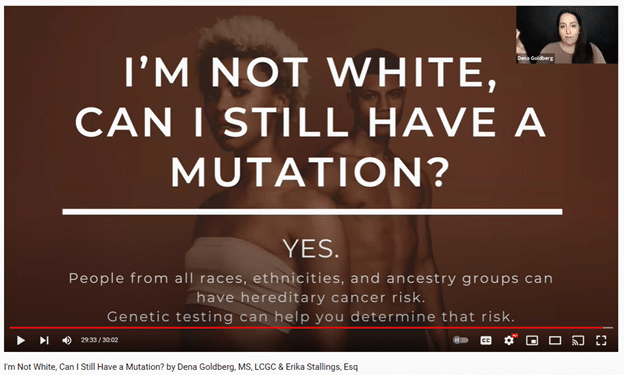

Adding to this burden is a common misperception that inherited mutations are not common in Black people. Yet the prevalence of BRCA mutations in the Black community is at least equal to that of the non-Jewish, white community. Some doctors and patients believe that genetic testing is for white people. Consequently, Black people are 16 times less likely to be referred for genetic testing. A person’s race, however, should not exclude them from genetic testing, because someone’s race does not correspond with a greater or lesser risk for certain genes.

In their session, “I’m Not White, Can I Still Have a Mutation?” genetic counselor Dena Goldberg, CGC and patient advocate Erika Stallings talk about these misperceptions and discuss the health implications of these biases for people of color.

As a Black woman with a BRCA2 mutation, Ms. Stallings talks about her family history with breast cancer and her journey to becoming an advocate. Her mom was first diagnosed with breast cancer at age 28 and had a second diagnosis 14 years later. Subsequently, she had genetic testing and learned that she had a BRCA2 mutation. When Ms. Stallings underwent genetic testing, she was struck by the lack of stories from other Black women with inherited mutations. As she says,

“Something that I think about a lot as it relates to my mom’s journey and my own journey is how much luck and privilege and access is involved in being able to get this information.”

This led her to share her story publicly and become more involved in advocacy and raise awareness about the importance of people of color learning their risk. In her own words,

“Knowledge of family history and utilization of genetic counseling and testing are really important tools for cancer risk management and risk reduction, but currently those benefits are not being fully realized in the Black community.”

Ms. Stallings recommends the following:

- If you are a patient with a family history of cancer on one or both sides of your family, think about genetic counseling if you haven’t already.

- If you are a genetics expert or a physician or a researcher, think about the unconscious biases that might be at play. Consider the recommendations that you make to your patients and the assumptions you make about who is interested in genetic counseling and testing because the research shows that Black women are overwhelmingly enthusiastic when the benefits are explained and offered to them.

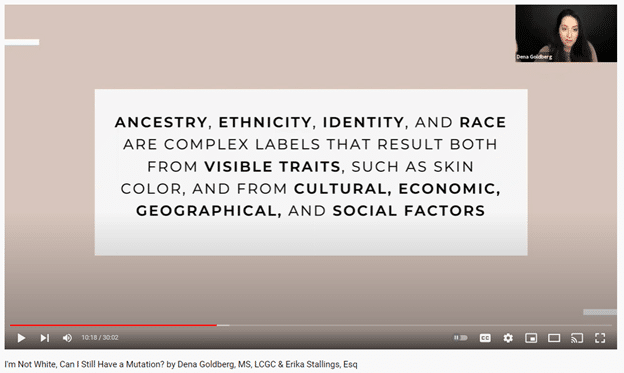

Ms. Goldberg’s discussion begins with definitions and descriptions of terms, including ancestry, ethnicity and race, and she reminds us of the complexity of these labels.

Ms. Goldberg points out a common assumption that people identify with their majority ancestry.

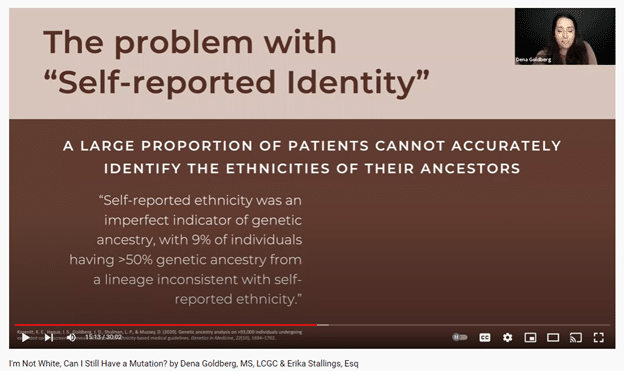

She presented a study conducted by a lab that concluded that 9 percent of people had genetic ancestry that did not align with their self-reported ethnicity.

Ms. Goldberg points out the challenge when healthcare professionals and doctors use popular notions of race to predict whether a person may or may not have increased risks for a mutation or cancer. This is not an accurate way to assess risk, and it emphasizes that a person’s “race” should not exclude them from genetic testing.

Ms. Goldberg also emphasizes that inherited mutations have been found in people of all ancestries, although some groups are more likely than others to have specific mutations. For example, 1 in 40 people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent carries one of three specific mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Even though this is a higher frequency than most other groups, it can reinforce the mistaken belief that only Jewish people have mutations. This is not only incorrect but also presents a barrier to getting tested among people who do not have or are not aware of having Jewish ancestry.

Another barrier is that most of the genetic testing to date (about 80 percent) has been done in populations of European descent. This means that people of other ancestries may be more likely to receive inconclusive genetic test results known as Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). The more people within a population who have genetic testing, the more that scientists can classify these variants. Ms. Goldberg emphasizes that this is a problem because it causes disparities.

Ms. Goldberg reviewed some steps that are currently being taken and others that need to be taken to address these disparities. She closes the session by answering the question in the session title with a resounding “Yes.”

You can view the entire presentation here.

POSTED IN: Genetic Testing , Health Equity And Disparities

TAGS: Genetic Counseling , Genetic Testing , Health Disparities , Health Equity