PUBLISHED: 24th August 2020

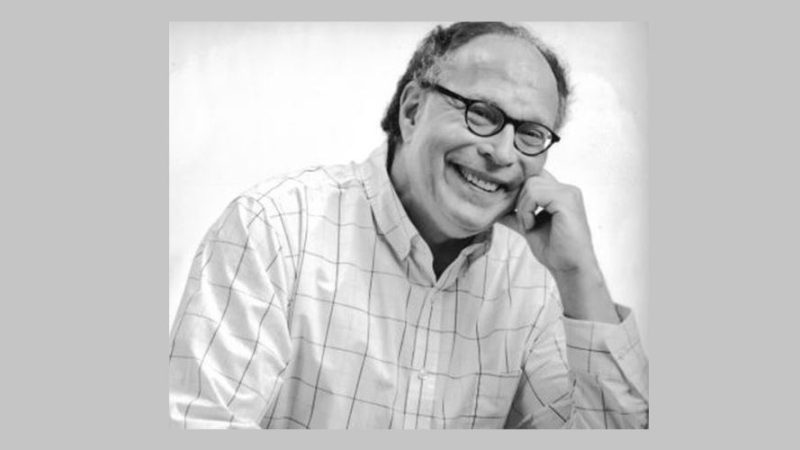

by Bob Riter

My breast cancer diagnosis

I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1996. At the time there was little information about male breast cancer and genetic testing for men with breast cancer was not routine. I had a feeling I might have a BRCA2 mutation because of my Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, my relatively young age at diagnosis and the fact that my mother died from pancreatic cancer. But, I was not tested at the time.

Another cancer scare leads to a surprising genetic test result

It was an elevated PSA test in 2020, 24 years after my breast cancer diagnosis, that finally prompted my genetic counseling and testing. Surprisingly, I didn’t have a BRCA mutation, but tested positive for an inherited CHEK2 mutation. Fortunately, I did not have prostate cancer, but my CHEK2 mutation likely increases my risk of developing it in the future. I wanted to participate in meaningful research that furthers our understanding of hereditary cancers, so I enrolled in a National Cancer Institute study for men at high genetic risk of prostate cancer.

Change happening for men in breast cancer studies

The way we discover new and better treatment options is with research. When I was first diagnosed with breast cancer, because so little was known about male breast cancer, I was treated as if I was a post-menopausal woman. I knew it was the best they could do at the time, but it wasn’t reassuring. There wasn’t good data on men with breast cancer because most breast cancer trials specifically excluded men.

Nearly 25 years later, this is beginning to change. The FDA now recommends that research trials for breast cancer drugs include men with breast cancer, and it is encouraging researchers to contact the FDA early in their research planning for guidance on enrolling men. The default is now that men should be included in all breast cancer trials, and there needs to be a scientific rationale if they are excluded.

To illustrate the importance of including men with breast cancer research, take the example of PARP inhibitors. They are relatively new and are used for breast cancers in individuals with BRCA mutations. Up to 14% of men with breast cancer have a BRCA2 mutation; we need to be included in the latest research if our treatment is to be based on the latest evidence.

FORCE is for men, too

To help others, I am a FORCE research advocate. I applaud FORCE and many cancer support organizations that called on the FDA to include men in breast cancer trials. The new guidelines offer men with breast cancer – and hereditary cancers more broadly – a brighter future.