PUBLISHED: 23rd October 2023

by Sue Friedman

This is the first of several blogs about my recent experience with thyroid cancer and how it prompted me to re-evaluate my thoughts about cancer care and patient advocacy.

Sitting in a hospital bed at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), I reflected on my 27-year cancer journey. I had been at NIH before as an advocate, but the experience was quite different as a patient.

Thoughts swirled through my mind, as I was still processing it all. But right here, right now, marked the culmination of eight months of tests, diagnosis, surgery, more surgery and even more tests. Finally, I would learn whether my poorly differentiated thyroid cancer had spread.

Echoes from my breast cancer diagnosis

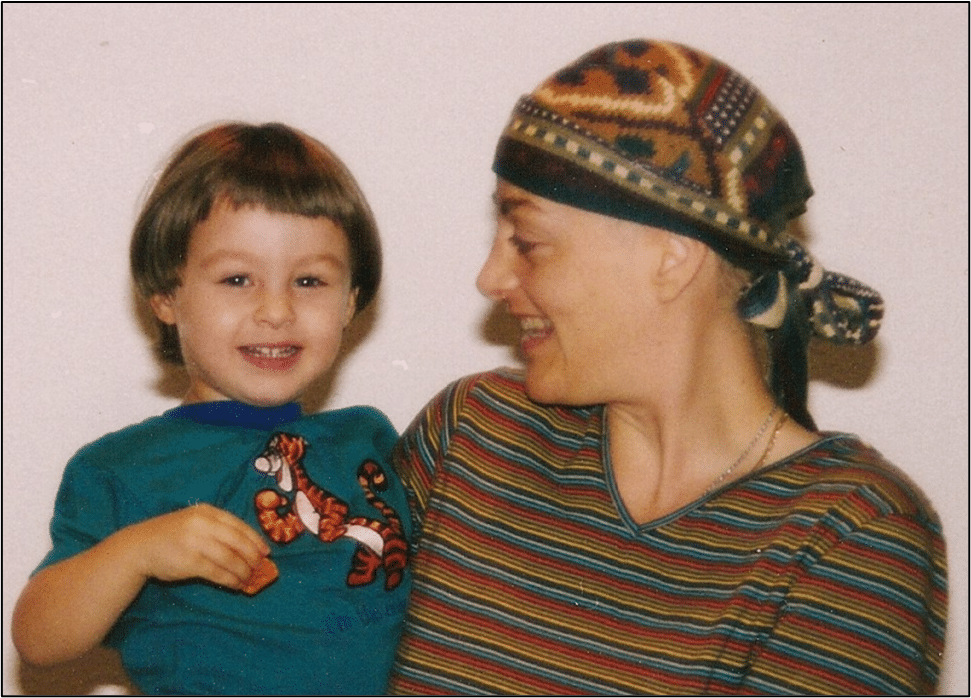

My advocacy journey, which parallels FORCE’s origin story, started in 1996. I was shocked to be diagnosed out of the blue with breast cancer at age 33. Because my initial diagnosis and staging were mismanaged, my healthcare team mistakenly diagnosed DCIS. Since it was scattered throughout my breast, I had a mastectomy, and I also chose to have reconstruction. Nine months later, however, the cancer recurred as a lump in my armpit. A reassessment and restaging determined that it wasn’t DCIS. I had invasive cancer, which by then had advanced to stage 2B.

My doctors missed all of the red flags for an inherited mutation. (Less was known about hereditary cancer in 1996, and genetic testing was fairly new.) Although I had no family history of breast cancer, I was young to be diagnosed with it, I’m Jewish and my paternal grandmother died of “abdominal” cancer. A series of second opinions followed by chemotherapy and aggressive radiation to my chest, armpit and neck at an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center followed. Genetic counseling and testing then gave me another surprise: I had an inherited BRCA2 mutation. Acknowledging my heightened cancer risk, I then had a salpingo-oophorectomy with a hysterectomy and a preventive mastectomy with reconstruction of my opposite breast to lower my risk of future cancer—all before I turned 36.

From veterinarian to patient advocate

The anxiety I felt during my recovery was overwhelming. My mind was on constant overload as I kept thinking about my recurrence. Information about hereditary cancer was scarce, and my questions about the mutation mostly remained unanswered. I was also dealing with the effects of treatment-related, early-onset menopause without the benefit of hormones, while making challenging decisions, worrying about my future risk for cancer and being concerned for my relatives.

Feeling isolated, anxious and uncertain prompted me to found FORCE on New Year's Day, 1999. I wanted to support and educate other people with inherited high-risk mutations and use my self-advocating experiences to help them advocate for themselves. I was motivated to help our entire community champion more and better research, medical options and access to supportive services and care. Shifting my focus from helping animals to helping people, I left my veterinary career to direct FORCE full-time.

Since then, the hereditary cancer community has been my teacher, inspiration and support. You’ve lifted me through surgical menopause, fear of recurrence and anxiety. Together, we’ve made an overwhelmingly positive difference. We’ve celebrated cancerversaries and taken pride in the numerous scientific and advocacy wins that have improved the lives of so many people and families in our community.

And I’ve been cancer-free for more than two decades...

…until this past New Year's Day—24 years since I began FORCE—when I felt a lump in my neck. Initially, it was diagnosed as a slow-growing thyroid cancer with a favorable prognosis. (I should note that no body of evidence has linked a BRCA2 mutation to a high risk for thyroid cancer.)

Falling Through Survivorship Cracks

Soon after my thyroid cancer diagnosis, I Googled my way to evidence-based websites about “causes of thyroid cancer” and learned that it can develop after radiation therapy, even many years after treatment. The radiation I received 27 years ago to prevent another recurrence of breast cancer in my lymph nodes likely caused this new cancer in my thyroid. However, my doctors did NOT tell me then or at any time after completing radiation that it elevated my risk for thyroid cancer.

It's beyond frustrating to know now what I didn’t know then: people at high risk for thyroid cancer can be screened. A physical exam by a doctor can detect thyroid lumps, you can learn to self-exam for lumps in your neck and ultrasound screening is the imaging of choice. When caught early—mine wasn’t—the prognosis from thyroid cancer is very good. Unfortunately, I never knew about any of these important steps that might have resulted in a more favorable diagnosis.

New diagnosis, new challenges

Believing that mine would be a run-of-the-mill cancer based on needle biopsies and ultrasound, I proceeded with a less aggressive partial thyroidectomy that removed only the cancerous half of my thyroid. My recovery was routine, and everything went well. I felt I had made sound decisions…until I received my pathology report.

Once again, I received an unexpected and shocking diagnosis: Poorly-differentiated thyroid cancer, an aggressive and rare disease that isn’t well understood. Other worrisome findings included a large amount of “vascular invasion,” meaning that cancer cells were found in the blood vessels of the tumor. Although the margins of my tumor were free of cancer cells, the border of healthy tissue was very slim, only about 1 mm.

Information about this type of thyroid cancer is limited, and what I found was not encouraging, so I stopped looking. Some health experts argue that thyroid cancer may be over-screened, over-diagnosed and overtreated—the same argument I heard about my initial diagnosis of DCIS. Back then, I ended up with an invasive and aggressive cancer, so perhaps I should have been better prepared for thyroid cancer and surgery. But I wasn’t.

Limited options

I was told that I needed a radioactive iodine scan to determine whether my thyroid cancer had spread. But first, I needed another surgery to remove the rest of my thyroid.

Following the scan, I would be treated with radioactive iodine. Normal thyroid cells and many thyroid cancers take up iodine, making this an effective treatment. But my type of cancer tends not to take up iodine. So the scan, as well as the treatment, might or might not be effective for me. Given all the advances in treatment options for early-stage, high-risk, aggressive breast cancers, I was surprised by this one-size-fits-all approach and the lack of treatment choices.

With nothing else available to keep early-stage, aggressive thyroid cancer from returning. I searched for clinical trials, but poorly differentiated thyroid cancer is rare, and large clinical trials aren’t studying new agents to prevent the recurrence of the early-stage disease. I also requested (and had to persistently advocate for) biomarker testing to see if my cancer had any mutations that might make me eligible for other treatment options. That testing found my inherited mutation, but not much else. Experts advised that my BRCA mutation likely didn’t cause the cancer, so targeted therapies like PARP inhibitors weren’t recommended for me in this situation.

Getting a second opinion

Getting a second opinion after a cancer diagnosis should be routine. Yet, that wasn’t my experience. Physical barriers to accessing care are real. So, when we advise people to, “get a second opinion,” it’s not always that simple. When I contacted an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center for a second opinion, I was told, “We need you here for five days; we're going to repeat every single one of your scans and tests” (which my health plan had already paid for once). When I asked why a re-do was necessary, they said the quality wasn't good enough.

I was fortunate to find a research study at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, where I had access to world-class experts. Although the study was not testing new treatments, they were looking at outcomes for people with thyroid disease. (Interestingly, my treating doctors at NIH felt that my original scans were high quality and did not require repeating any of the tests.) This allowed me to get a second opinion, have my second surgery, staging and, ultimately standard radioactive iodine treatment at NIH. The cost of my care was completely covered through the research study, as was some of my travel. I was extremely lucky, as not all studies cover additional costs or travel. The trial team was eager to work with my local healthcare team to ensure my continuity of care. It was reassuring to have healthcare teams that I knew would work together without rivalry to ensure that I received care that was best for me. That type of coordinated care should be given to all people with cancer.

In preparation for my treatment, I was put on a low-iodine diet for two weeks: no dairy, no egg yolks, no chocolate and nothing prepared with iodized salt.

Dusting off my coping skills

Halfway through my two-week stay at NIH–eight months after my initial testing and diagnosis—I would finally learn if my thyroid cancer had spread. The night before I received my results, I was feeling scared and restless. I went for an evening run to clear my head and pulled out all my coping tools to help me stave off the incredible dread I was feeling.

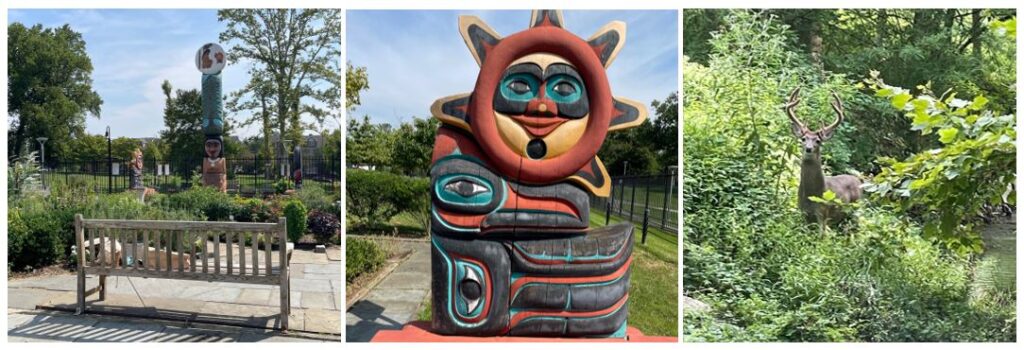

I created a new running playlist –“Burning Off Fear”– filled with the most upbeat, fast-paced music I could find. I wasn’t allowed off the NIH grounds, but there were plenty of running trails and interesting features to see. Near the National Library of Medicine, I discovered a sculpture garden with some healing totems. I stopped to recite my own version of the Serenity Prayer, picturing in my mind all my well-wishers and loved ones gathered around me.

Walking back to my room, I saw an amazing stag, regal and still. I pictured him my Patronus, sent to protect me. I felt more at peace and ready to face my results in the morning.

Finally, staging and treatment

After months of holding my breath and dealing with emotions ranging from anger to disbelief to fear to dread, I was finally granted enormous relief. Based on all the scans and test results, my doctors felt my cancer had not spread. They recommended high-dose radioiodine treatment.

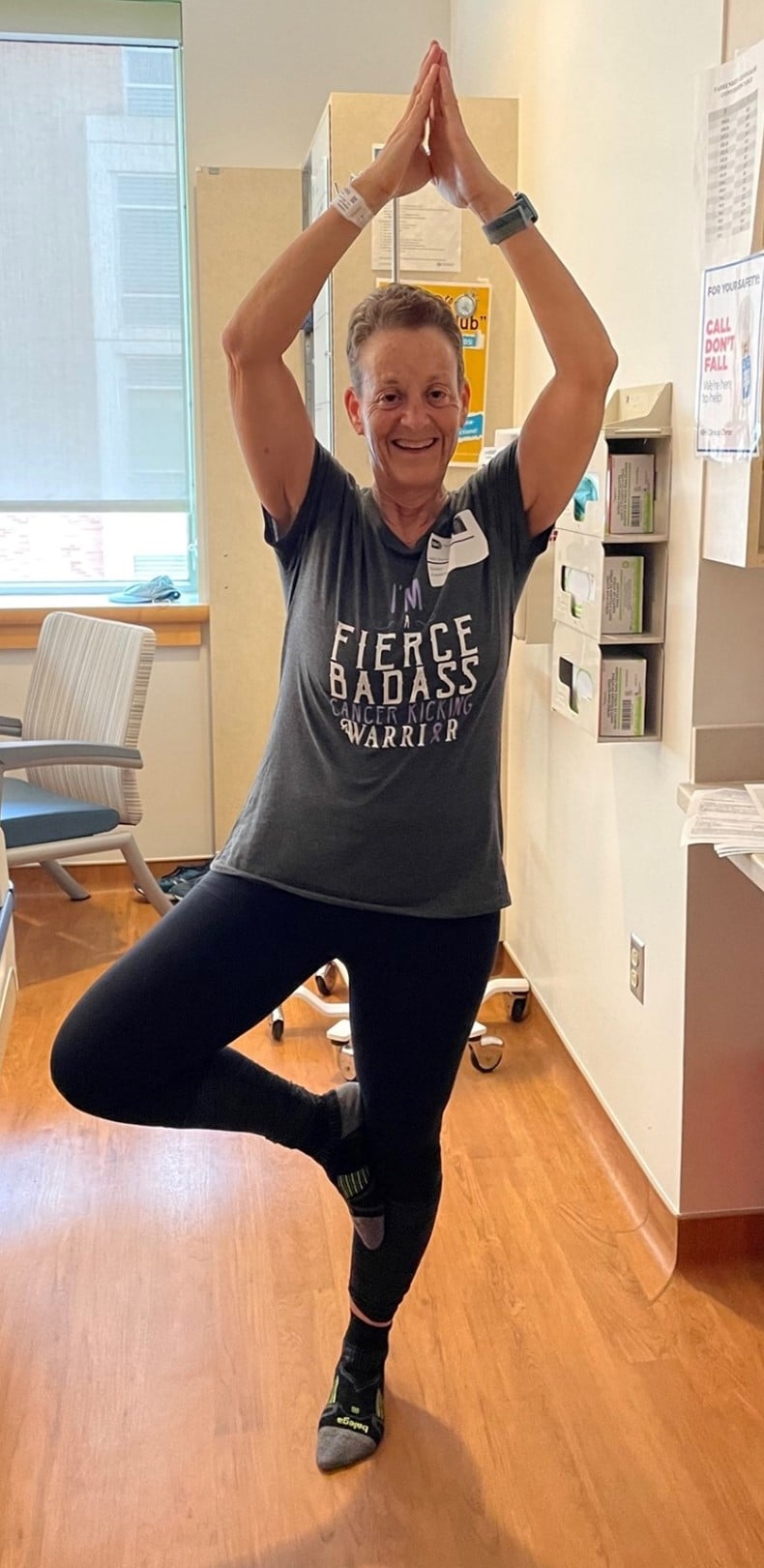

The iodine is given orally, followed by 48-72 hours in an isolation room. I could have no visitors, and couldn’t leave until I was no longer radioactive. I had my iPad, an exercise mat and a TV. I was told that sweating would help rid my body of the radioactivity more quickly. With very few options and little else to do, I worked out to aerobicize and yoga videos three times a day. The isolation room was stifling, but my treatment with high-dose radioactive iodine was tolerable. After 48 hours, I was released from the room and freed from my low-iodine diet. The first Starbucks latte, followed by ice cream, was heaven! I had one more follow-up scan and then, after 12 days in the hospital, I was able to go home.

A month after my treatment, I am still processing my experience. I learned so much, and I hope to channel much of this new knowledge and understanding into becoming a more effective advocate for this community that I love.

I feel great, and I am profoundly grateful. I’m still considered at very high risk for recurrence, and I’ll be followed with regular bloodwork, ultrasound and scans. But at the moment, I am cancer-free and done with treatment.

I know how fortunate I am on many fronts. As a veterinarian, I have a medical background, and I have been an advocate for 25 years, so my knowledge of cancer is significantly more than the average patient. I know lots of people as well as some of the top cancer centers and available clinical trials. I know how to navigate the health system, at least in general terms, and I have the resources to do it. I‘m outspoken and know how to ask questions about topics I don’t understand. Given all that, and all my privilege, at times this has been a very scary and disempowering experience. And that is humbling.

Sue Friedman, DVM is the founder and Executive Director of FORCE. She is a 27-year breast cancer survivor, and a less-than-1-year thyroid cancer survivor with an inherited BRCA2 mutation.

POSTED IN: Cancer Treatment , Screening And Prevention , Hereditary Cancer - General

TAGS: Screening And Prevention , Patient Advocacy , Cancer Treatment

12 Comments

November 1, 2023

Thank you for telling this story. I'm sure some folks will now learn methods for self-examination for neck lumps because of you and advocate for themselves if they've had radiation that could influence their thyroid.

sally james

Reply

November 2, 2023

I am so glad that you are helping those with cancer. Losing my husband Tom to thyroid cancer in 2001 was devastating. I am sure Piri has told you that story. You are a wonderful advocate. Please continue with this great work. Praying that all the work Force does is successful.

Marilyn Welcsh

Reply

November 13, 2023

Thank you for sharing. I am going through this, now. I had one side of my thyroid removed and will have the other side removed next week. I will also have RAI treatment. I am a very healthy/active 38 year old woman, and I had to push, advocate, research and ask the right questions. I have an inherited CHEK2 mutation, but the doctors do not believe that it is related to that. Any cancer journey is humbling and scary. It helps to see others coming out alright. Thanks

Tiffany Johnson

Reply

November 13, 2023

Thank you for sharing your story Sue and best wishes to you. I am beyond grateful for your generosity and foresight in founding FORCE. I learned this summer that I have an ATM mutation. FORCE has been invaluable. My Dad and one of my sisters were/are veterinarians. I appreciate that you gave up your veterinary career to lead FORCE.

Lauri Perman

Reply

January 3, 2024

Sue, I have been "with you" since 1997. I know your story, similar to my own.i had a new breast cancer in 2019, after 22 years of being cancet-free. The cancer developed deep near the muscle in the same side so the mastectomy did not prevent the cancer. So for the 2nd time in .my life I had radiation. I will find out about checking the thyroid Wishing you a full recovery

Betty

Reply

November 1, 2023

I applaud you on this journey of self advocating. I was dx with invasive breast, had bilateral mastectomy with breast implants. Being BRCA2, I was advised have a total Hysterectomy (age 59), in which I did. This yr my PCP felt a lump and I has a thyroid scan which showed a cycle. I was referred to to an ENT. Sought of afraid what might I be told, I was assured that it's nothing and nothing to worry about. This is without a bx being taken. Further more I was assured that if this is ca " I'll go down in the grave with you." Wow! I consulted with other health care professionals (survivorship, med onc) and was advised that I shouldn't worry because it's nothing. All that to say, I've let it go and just God.

DANIELLE BAKER

Reply

November 2, 2023

I had a similar but reverse experience. I was diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer in 1992 which was treated with surgery. Then in 2017 I was diagnosed with stage 2 invasive ductal carcinoma. I have not tested positive for the BRCA gene but I do have ATM. (I likewise spent 10 years in the veterinary field)

Cheryl Terpak

Reply

January 8, 2024

Thank you Sue for sharing your story! Thank you for all you do at FORCE for everyone! FORCE is absolutely awesome! Praying for many years of being cancer free for you! Thank you!!

Linda Vos

Reply

January 9, 2024

What impressed me the most was your optimism and tenacity during this difficult path. Your ability to see the bright side of a bad circumstance and convert it into an opportunity to learn is very remarkable. Thank you for sharing your experience; it reminds us all to face life's unexpected obstacles with fortitude and positivity. I wish you continued good health and look forward to reading more of your posts.

castoravon

Reply

April 14, 2024

I just love your story! All of it. And I am thankful for your involvement of FORCE. A hundred years ago( I’m 41) I was a veterinary technician for a multi practice hospital. Internal medicine,emergency, reproduction, advanced surgery, rehabilitation. So my trainings to support the animals in those areas transferred ( for the most part) to years later advocation for myself. Mainly in using/ understanding medical terminology.

SumofAllParts

Reply

November 1, 2023

Thank you for sharing your journey, Sue! Your resilience is truly inspirational to many, especially as you shed light on your recent thyroid cancer experience. Earlier this year, I faced a thyroid cancer scare, which culminated in a partial thyroidectomy. Fortunately, I was diagnosed with thyroid nodular disease instead of cancer. Yet the emotional ups and downs—from discovering thyroid nodules to awaiting the results of ultrasounds, biopsies, and post-surgery pathology—were intense and draining. The silver lining was that this experience, combined with my preceding Lynch Syndrome and CHEK2 diagnoses, led me to FORCE and now I am a P.A.L (Patient Advocate Leader). I'm profoundly grateful for you, your team, and the incredible fellow advocates!

Sara Kavanaugh

Reply

April 22, 2025

I am having a total thyroidectomy Papillary stage BAD. Lifetime of Hashimotos and despite education here I am. So now I guess I shall have to stand up for myself better! So glad you are ok

Lesley Yoder

Reply