PUBLISHED: 1st April 2019

by Lisa Schlager

Breast implant safety is a hot topic. We recently published an XRAYS review that shed some light on the importance of well-designed research and reliable information about breast implants. Last week, I attended and made public remarks at a 2-day meeting on breast implants hosted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA staff and members of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices Advisory Committee were joined by industry representatives, professional societies, and members of the public to review the safety of breast implants and surgical mesh. The meeting also covered screening for implant ruptures, patient education, and informed consent.

HISTORY of Breast Implants:

In the U.S. last year, more than 100,000 women underwent breast reconstruction after mastectomy, and about three times that number had breast augmentation. Breast implants have been widely used since the 1960s. Since then, there have been many anecdotal reports by women who blamed their implants for rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and numerous other autoimmune disorders. Despite hundreds of studies, no connection was made between implants and major diseases or health conditions. In response to these safety concerns, between 1992 and 2006, the FDA restricted silicone implants to use in clinical trials. That restriction was lifted in 2006, and newer-generation silicone gel implants were approved. As a condition of the approval, the FDA directed the manufacturers to conduct post-approval research to prove long-term performance and safety of the devices.

Recently, the FDA issued warning letters to two implant manufacturers, Mentor and Sientra, for insufficient follow-up on the mandated post-market approval studies. The agency criticized these companies for failing to enroll the targeted number of patients and the lack of quality and completeness of report data. The companies were also cited for a lack of details regarding complications and patients who were excluded from the studies. At the recent hearings, both companies said that it has been difficult to enroll and retain study participants.

RISKS of Breast Implants:

As with any surgical procedure, breast implant surgery carries risks. In addition to the immediate risks of anesthesia, implant procedures include the risk of infection, hematoma/seroma (blood/fluid collecting around an implant), necrosis (skin death), and capsular contracture (surrounding scar tissue that squeezes and distorts the implant). Recently, two more severe complications have drawn attention: these were a focus of the FDA hearings.

BIA-ALCL

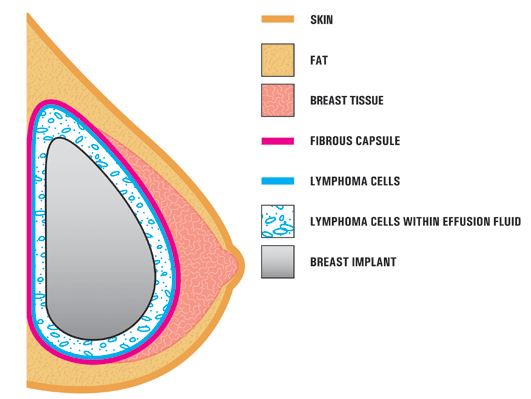

Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) is cancer that may develop in the capsule of scar tissue that typically forms around breast implants after reconstruction or augmentation. BIA-ALCL has been primarily linked to textured implants—“highly textured” implants may be associated with a greater incidence—the FDA reported that it has received only a few reports of BIA-ALCL involving smooth implants. Textured implants account for only about 12% of the implants used in the U.S. They are much more common in Europe, where they represent over three-quarters of the market. While some meeting participants proposed that U.S. regulators block the use of textured implants, others suggested that more data is needed, because the risks are quite small and textured implants may produce better results for certain patients, sparing them from repeat surgical procedures which also have risk.

The estimated lifetime risk of BIA-ALCL less than 1%. In February, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons said it was aware of 688 cases of BIA-ALCL worldwide (30 countries), with 17 disease-related deaths. Research indicates that the average time between surgery and BIA-ALCL diagnosis is about 9 years. If diagnosed early and treated properly, ALCL is curable; over 90% of patients are disease-free after 3 years. However, concerns about misdiagnosis were discussed at the FDA meeting, as many health care providers are unfamiliar with the condition and how to identify it. The FDA recently sent a letter to health care providers in an effort to increase awareness. FAQs and patient resources have been developed, as well as information and continuing education for clinicians.

Breast Implant Illness

Breast implant illness (BII) is an umbrella term used to describe a collection of symptoms and illnesses that may be related to breast implants. Affected women experience a variety of issues, including fatigue, brain fog, rashes, joint pain, gastrointestinal issues, and more. Symptoms vary from patient to patient. It is difficult for scientific research to definitively link any of these conditions to implants, as they frequently occur in women without implants—especially those who have undergone cancer treatments. Some women experience immediate relief of their symptoms when their implants are removed, but others don’t.

In some women, these problems may be an autoimmune or allergic response to a foreign object (implants) placed in the body. Currently, there is no established medical definition or diagnostic criteria for BII, but many are calling for better research and informed consent. Women with a personal or family history of autoimmune disease or allergies are encouraged to discuss this with their surgeons when considering breast implants.

Implant Rupture

Implants are not intended to be permanent devices; the typical lifespan ranges from 10-20 years, although they often need to be removed and/or replaced sooner. If an implant tears or develops a hole, it is called a rupture. Ruptures occur in both saline and silicone breast implants. Ruptures usually occur with older implants, but earlier ruptures may develop due to a defect, surgical error, or blunt trauma from a fall or accident.

Saline implant ruptures are easily identified. The breast rapidly deflates as the saline leaks out. Ruptures in silicone gel implants are more difficult to detect. Some women encounter symptoms, including lumps in the breast, distorted breast shape or asymmetry (different sized or shaped breasts), pain or tenderness. These are “silent ruptures”—women and their doctors may not notice them. Removing and replacing the implant is the only way to fix a rupture.

Experts disagree about the best regimen for monitoring women with breast implants. In addition to a yearly clinical breast exam, the FDA recommends an MRI three years after implantation and once every other year after that. MRIs are expensive and may not be covered by insurance, so some experts suggest that they should only be used when a rupture is suspected. Other organizations believe that mammograms and/or ultrasound are sufficient for routine screening. This lack of consistency causes confusion, so FORCE encouraged the FDA and other stakeholders to develop consistent guidelines for recommended follow-up care for women with implants.

Surgical Mesh

An acellular dermal matrix (ADM) is a sterile tissue substitute made from human or animal tissues that have been stripped of their biological components, but still contain collagen. Some ADMs are also manmade. A majority of implant-based breast reconstructions now include an ADM. Used for over a decade in breast reconstruction, ADM has dramatically changed how implant reconstruction can be done. It provides an additional layer of tissue between the skin and the implant tissue, which can reduce implant wrinkling and rippling. When used with tissue expansion, it shortens the process, and in many women, it eliminates the need for expansion (direct-to-implant). Overall ADM tends to produce better aesthetic results, and it is less affected by radiation than implant reconstruction without it.

While ADM is FDA-approved for use in other indications, such as pelvic, abdominal, and burn surgeries, it is not officially approved for use in breast reconstruction. The FDA expressed concern that the use of ADMs may complicate the ability to determine the cause of implant-related illnesses, and is asking manufacturers to launch studies on its safety and efficacy in breast reconstruction. Ultimately, the agency may require approval for using ADM in breast surgeries.

Closing Thoughts

A few clear messages emerged during the 2-day meeting:

Women are often unaware of the information they need to make an informed decision about receiving breast implants. Improved informed consent might include more patient-friendly materials in writing and multimedia formats, such as video and interactive web-based platforms. Informed consent is not a piece of paper; it is a process. Physicians must help women better understand the benefits and risks.

Better transparency, tracking of implants, and outcomes is also needed. At the meeting, panel members and the public expressed frustration with FDA’s limited knowledge and long-term data. The FDA and manufacturers have not been diligent in gathering and reporting adverse event information. About 30% of the time when implants are removed, the only information is the type of implant; details about cause is often lacking. Tools to facilitate improved collection of this and other information may include implant registries, phone apps, and artificial intelligence such as the Aesthetic Neural Network (ANN), which can gather and analyze de-identified data from electronic health records in plastic surgery practices.

Experts also disagree on how to best monitor women with breast implants for rupture and/or cancer—the FDA, American College of Radiology, American Society of Plastic Surgeons and others support different recommendations. This can hinder early, accurate diagnosis of complications. We need consistent guidelines on how and when women with implant-based reconstruction and breast augmentation should be screened.

Finally, independent, high-quality research is crucial. Only with well-designed, long-term studies will we better understand BII, BIA-ALCL, and the overall safety of implants.

FORCE will continue to follow this and related issues, and will keep the community informed. Be sure to regularly check our XRAYS reviews and website for additional, evidence-based information.

POSTED IN: Breast Reconstruction And Going Flat

TAGS: FDA , Reconstruction Or Going Flat , Breast Implants , BIA-ALCL